A system may have a correctly planned exit strategy and expectancy of a positive win rate and win/loss ratio to produce. If it doesn't, you better figure out how to come up with one. If you are lost on where to start to start learning expected win rates I will give you a great example of a strategy.

For example, IBD index gives a trade management strategy that has a combination of a 25% trailing stop and 8% hard stop (that is later replaced with the trailing stop after it gains enough to replace it). Such a system stops out around 75% of the time for a loss, but the remaining 25% it still gains enough to average greater than 5 to 1 return to risk. Basically, this system will largely win more than it loses if you don't get carried away and risk too much.

The first criteria towards "calling an audible" must be that wherever you take profits MUST be such that your strategy as a WHOLE must be expected to be profitable on it's own without consideration for bankroll size. Don't think about the individual trade that takess a gain at 10% or whatever, because only a certain percentage of your trades actually will even get to that point. Many others will turn against you and stop out at 8%. As such, you have to think about the entire trade.

A lot of people say the false rhetoric "you'll never go broke taking a profit". You should laugh when you hear it. That's like saying "you'll never lose money with a hole in your pocket while your pants are burning by putting more money in your pocket". Saying what they're saying is basically proposing that "you can make money while it's at risk by taking a profit whenever you want". That suggests that it is acceptable to have a strategy where you stop out for a 10% loss when you are wrong and take profits up 2%. HA, liar, liar, pants on fire (hole in the pocket and all).

You MUST account for the fact that you won't always be right immediately. Everyone wants to abandon a quality strategy because the fear of having a gain turn into a loss overwhelms them and they don't have a fundamental logical and mathematical system for performing analysis and don't have a clue where to start. That's what this post is for.

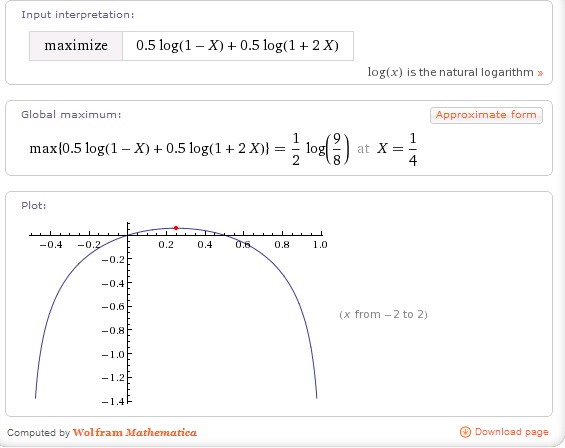

So how do you determine if the strategy as a whole can be profitable? The function is knowing probability of a win, amount you'll lose, and amount at a minimum given that information you can take profits. Or you can look at the price right now, the stop loss, and what your odds of success need to be for the strategy to work, and compare that to your estimated odds. To determine if the strategy is profitable, simply ask yourself the question, "based upon your current stop and taking profits at the current price, what win percentage do you have to have to break even?" Once you answer it, you can compare that number to the actual long term win percentage average of your strategy and see if it's even above a break even strategy. You can also instead run the calculation based upon the win rate and determine what your upside needs to be to break even, then make sure your upside is above that before selling.

So if your win rate is 25% then maybe selling early may enhance your winrate slightly, but not all that much. In the strategy above, if you win 25% of the time, how much do your wins have to outweigh your losses on average to break even?

25% rate means 1/4. Means you after 3 losses, on the 4th you have to win it all back. In other words, the WIN must be 4 times the average loss. The average loss is a bit greater than your stoploss if it is a flat stop since the possibility to gap below the stop is possible. In this case (following the information provided at IBDindex.blogspot) it switches to a trailing stop so it probably is greater than the stoploss of 8%. In fact, we can see the average loss on $1000 invested in the S&P is $78.62. Which translates to 7.862%. So to break even on a 25% chance of winning we need to make 3 times that amount or $235.86. In other words, you have to have a 23.586% gain going (after considering fees) in order to break even. Really, you may want to look at the win rate of just leaving a flat 8% stop with 20% profit target since that is a more realistic look at your actual win rate. Your win rate jumps up above 30% to around 33% and as such you can lose twice and win on the third and you need to at that point win it all back. As such your win must only be 2 times your stoploss or 8*2=16%.

However, there is still a problem with this line of thinking. First of all, To make up for a 10% loss you need an 11% gain so your gains must be skewed slightly to the upside in order to break even. If you risk too much the volatility to your portfolio is too great and it actually becomes impossible to make up for your losses. Plus backtesting often gives you an uncertain view of the future, and if there is one thing you learn while trading it's that uncertainty requires greater caution. Also, there probably is a better than break even strategy available, so just meeting the minimum threshold probably isn't enough cushion. In addition, money management also may suggest your position is too large with only a slight edge, and as such for your given position size to be correct to make money due to volatility, you may have to have a greater edge. Finally, you must also account for the fees, so if you haven't done so already, you need to.

The mere act of running the numbers will help with indecisiveness and uncertainty that randomness may convince someone to sell too early to have an effective strategy or let the losses go. You can only let the losses go so much before your average gain on the upside isn't enough to make up for letting the loss go.

Here's a good image from offroad finance.

What you can see is what happens at first when you bet too much is your long term expected rate of growth declines to less than maximum, but as it continues to increase the bet size it soon goes sharply negative.

You may not notice it as negative because you could produce a win that's much larger, then you produce a loss and you have trouble getting back to even after several trades without knowing why. Sometimes you'll spike above where you started. It's easy to fool yourself and think you made the right bet.

But back to the system. For the strategy to be profitable, it not only needs to be such that a bet at a FIXED amount will win more than it loses over time, but such that a bet at THAT percentage of your portfolio. In other words, if your edge of selling out early is small enough that it doesn't allow the kind of initial betsize you started with, you still can't call an audible and sell. I would be a bit flexible if the betsize is such that it would produce somewhere between the optimal bet and twice the optimal bet (beyond twice the optimal betsize return shifts to negative).

Since you may only audible on SOME of your bets, you may offer a little bit of leeway as well since the remainder of those stopping out you wouldn't have been convinced that calling an audible was best. This is complicated to explain since we are dealing with a theoretical position that could have "in another universe" gone against you. Or in other words, one of the possible outcomes where you would call an audible end up stopping out before you get the chance. But sometimes the ones in which you would ride the trade all the way out until the target if they break that way you might see stop out as well. The overall system must be a composition of ALL your trades, so you may try to factor in some of the good and allow a bit more room. If you take your normal win rate when you let the system work and you notice calling an audible at that win rate will break even after fees and expenses, I think it's safe to say that for whatever reasons you notice that may change your odds, plus the fact that you will only audible on very few will make it better than break even by calling an audible, but I still would leave a little cushion, and also have a system where you pick winners with more frequency than the numbers above (but still run calculations based off it)

However, this can often set a bad precedence. If this individual trade is not profitable if made every single time while including all those that WILL go against you... Or if the position size is too large, then you should not have made it in the first place. Trying to change it now isn't going to make the overall history of trading more profitable, only letting it ride out to a much larger price target will. Running the math should be done if it allows you to stay in trades longer as you should, not as an excuse to sell early.

You can consider taking HALF of your profits early. In this case you may want to consider what will happen with the other half, but that in my mind is too hard to predict mid-trade. Instead, I would just make sure that after accounting for ADDITIONAL fees, you make sure that HALF the position size would have been profitable and acceptable to trade in that matter. In other words, if you trade a 4% stop loss in a system and take profits at 20% instead of the usual 25% first decide if you profit enough (1/6th of the time or around 17%). That is likely true, but the next question is, can your system at your win rate (perhaps 25%) justify a position size equal to one half your starting position size? The strange thing that happens is that TOO SMALL of a position can be equally as dangerous as too large as you have to be concerned about fees, and fee has to be small enough as a percentage of your position size. Yet your position size as a percentage of your portfolio must also be small enough.

In the example's case, if you have 5k bankroll the cost is $5 per trade ($15 to close a trade where you sell half midway through) and you started with 40% of your bankroll (and now are selling 20%) then you can certainly place the trade. There is a range where the calculation gets a little murky because Do you use the initial 40% and $15 fee? $5 fee and 20% at risk? 20% at risk and $15 fee? Do you calculate the average of the regular system and the one you have effectively created? I'm not really sure, I just know I would rather take the safe trade that I KNOW is profitable for all of them.

Always add a "margin of safety" in your systems. It's better to take 3 trades that you CERTAINLY make a profit than 100 that you only THINK you are. If you take this approach and factor it into your calculation, you will think more carefully about position sizing in the first place, you will be more strategic about adjusting your stops and thinking mathematically, and it will prevent you from selling too early. You also may take that approach and not take trades that you aren't comfortable with.

Rarely is it correct to call an audible. Either the system works or it doesn't, If you are not able to ride out the times when it appears the system may fail, then you are not ready to trade the system in the first place.

Now granted, yes, you certainly can call an audible on the side of taking gains too early, but if you are going to do that you also need to find ways to call an audible and let the gains run on longer and cut your losses much more quickly. This is not easy to do, and as such you shouldn't take many audibles. I could have just said that right off the bat, but I feel the best strategy in helping me avoid taking the gains too early has been to understand the mathematics of it. Nothing else has worked. Taking this approach from the start of letting the mathematics and system dictate your actions is fundamental to success.

But there are many more systems and certainly are some times when calling an audible is correct.

I'll give you an example. I took a system that basically is very similar to the high tight flag system. The consolidation didn't last long enough to officially qualify but it is close enough for me. Sometimes the stock may take 3 months rather than 2 to make 90% instead of 100% move but it's close enough for me. Anyways, I took a trade in VNDA and correctly called an audible.

I took the trade intending on buying $.10 above the breakout. I got filled at $10.62. The stop was basically at $10 or $.62 or 5.84% or nearly 6%. Some would be below, some would be above. Right after buying the stock took off that day. The next day the stock had ran out of steam and barely seemed to make new highs. But at $13, it was up $3 4.84 times my risk of $.62, I could afford to lose $.62 4.84 times and then on the next time (5.84th time) win it all back. In other words, my odds needed to be 1/5.84 or around 17% or better for the trade to be profitable. It was, no question. The position size was very healthy, but at even a 25% chance of winning it wasn't so large that I had risked too much so I could sell it.

With that criteria out of the way NOW I can try to be subjective. I have already ran the numbers. Now "Is this the next AAPL running up from $10 to $700?" doubtful. "Is there a significantly good chance I will get an opportunity to buy lower anyways?" Not sure, but I think so. "Is the AVERAGE trade that I took going to give me significantly more?" Maybe not. The high tight flag with perfect qualifications show an average rise of 69% but after looking at the individual numbers and considering a 25% trailing stop even the rare up 75% stocks will pull back to up only 31.25%. But this could be looked at as a bull flag, and if that's the case the expectations are much lower. If I have a 25% trailing stop, I need the stock to go up 60% before it can pullback and stop out at a 20% gain, so by selling now I am way ahead of schedule. If I make trades like this rather than the typical trade that doesn't peak out for a full 39 days even though the expectations per trade may be better if I stick with a trailing stop, the speed of being able to make trades like this would greatly favor selling now.

Are there significantly greater risks of staying in this stock? Absolutely, it could gap down the next day well below my stop as is the case with biotech. On the other hand, because of this risk you might argue that I need to let the winners run. Do I have a bit more capital than I should at risk and do I need to raise cash? In this case the answer was YES. I could handle this by selling or by instead putting on a hedge with the remaining cash so I reduce upside exposure. I believed selling was the better option.

I may be a bit results oriented here since it was a fantastic trade and I avoided a lot of trouble. I may have just gotten lucky and the majority of the time I make this same or a similar audible it may go horribly wrong against me to the upside and I may miss out. It's hard to say. However, I would be more than satisfied with a system that produces wins of 22.4% even 25% of the time every 2 trading days or around 125 trades a year. But if the odds of having a successful trade were 30% the return would be awesome. Even so, the odds are I didn't make a huge mistake and the system wouldn't have been significantly unprofitable and there is a very high likelihood that that strategy to sell and call an audible there was acceptable.

I don't know what the actual odds are, only that I imagine they would have to be better than the typical trade of 25% and that when you combine the possibility of being able to get back in the trade lower, it is much more profitable. The setup was never right to get back into the trade but I believe were the stock to go much higher there was still are reasonable chance that it would have offered another entry. So this audible was really a no brainer as "not a huge mistake", even though I certainly could see a very legitimate argument towards not making it. In this case I believed that the strategy of taking gains in this case was more profitable than letting them ride. Had the rise been more gradual, ironically I would have been more willing to stay in. It's the stocks that launch way up too fast that don't tend to continue their momentum. The slow crawl upwards tends to continue, but the sudden spike gap after a significant move is dangerous.

Of course "when not to call an audible" when you think you should, will be an event you notice more often. I was in ZLC, had an above average position and considered selling half after a quick one day spike. After doing the math I needed a 40% win rate for it to be even profitable. It was close but I believe that would be far too aggressive, and not provide that margin of safety, especially since that wouldn't be able to support the half of a position size and letting the stock ride is certainly more profitable.

Hopefully as a result of this long post you learn a lot about structuring the trades AFTER THE FACT so that you are not reacting based upon emotion. Hopefully you can avoid putting too many trades at once and manage money better as a result of this knowledge, but of course, as always this is informational purposes only, and a journal to myself, not you, so proceed at your own risk.

No comments:

Post a Comment