The major institutional investors with tons of capital need liquidity to trade in the size that they want. They simply can't buy at the market like everyone else. There has to be enough people taking the other side of the trade, otherwise, no transaction can take place. For every buyer there must be a seller and vise versa.

So even though it seems like 100s of millions of shares of volume everyday is enough, if 100M extra shares wanted to get to work, they wouldn't find anyone to take the other side of the trade at the stocks current prices. Any inbalance of buying demand and selling demand will have to be settled by adjusting the price of the demand in order for any "trade" to take place. In other words, if the market will sell you 10M shares of a stock at $50, and you want to buy $20M, you only are able to buy $10M and after that you have to bid higher and higher until someone says... okay, I will sell to you at $55 or whatever.

This is what drives price, and "volume profiles" are often a clue of the market environment and what can come next.

Then there are even bigger players than the ins bond holders and the foreign exchange markets. There are currencies for trading goods and services, and then there is currency for "parking" capital to preserve value. The largest central banks will "park" their money in dollars because it is the world reserve currency. When they have difficulty finding demand for their local dollars, they switch to US dollar, to park it for safety. Basically the US dollar will always be allowed for trade by all countries as long as this remains.

But when it comes to the major global investors who participate in multiple asset classes, particularly in low liquidity markets, they require large DEMAND for either shares, or supply of shares (demand from shareholders of cash).

Now I bring this up because there also exists an interesting phenomenon. if there is a huge amount of volume and price drops below where it was where that volume existed, you now have a huge number of people underwater in their position. If there are no history of those wanting to buy at lower prices, there is likely to be more selling pressure UNTIL areas inwhich buyers IN SIZE are willing to pick up shares.

Take entire markets of gold represented by GLD, and bonds, represented by TLT. They once both looked like this.

You could almost see what was coming.

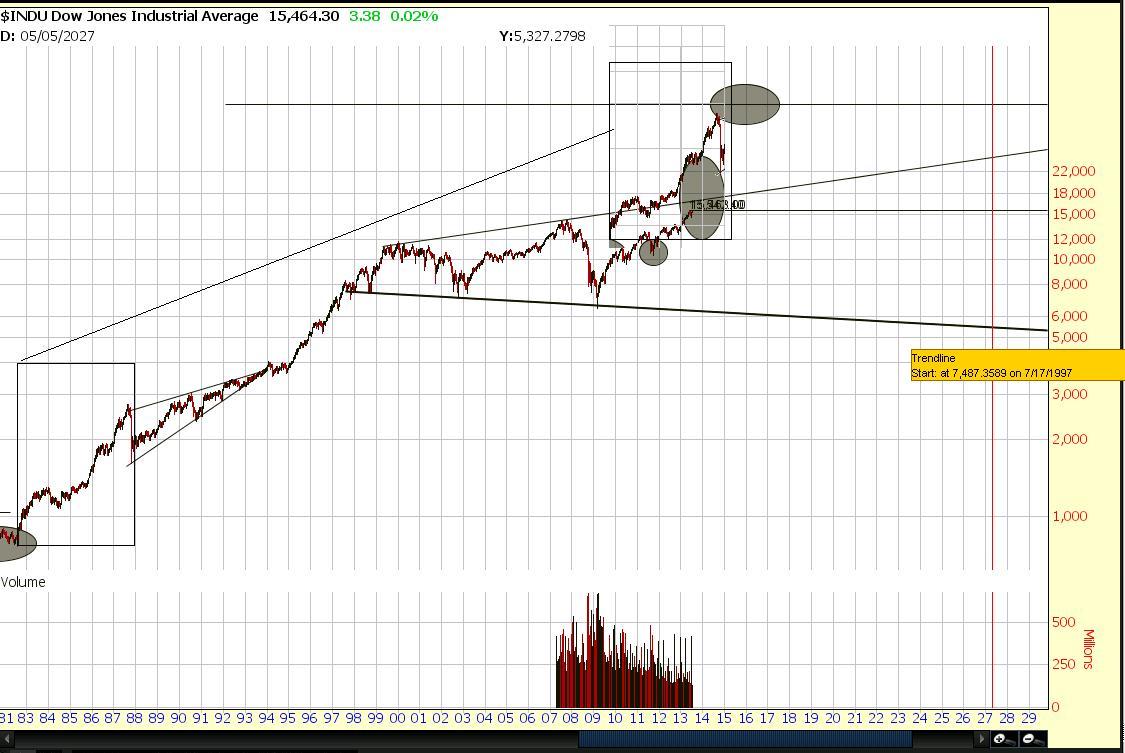

Keep these lessons in mind when you look at any market. For example, lets look at the recent action in stocks.

Now it's even more powerful when you aren't just applying this understanding in isolation. Instead, you should look at it from the institutional investors point of view.

If I was them and I had bought the 2009 lows, I know that I could not get out without stocks dropping to dow 13500 and lower or DIA 135 and lower. There are conditions where it may be worth selling, but those are hard to envision from our perspective. However, what one can notice is that there may be some fear right now. The institutional investors may be looking ahead in the calendar. There are European elections September 22nd and the US is facing a budget deadline October 1st, lead by a group of extremes on both side, neither of which have shown any willingness to compromise.

I certainly would want to reduce my risk exposure leading into these events, but only to be prepared perhaps to buy significant weakness.

The problem with suggesting just that markets will sell off is that it lacks the answer "where will that capital go". Will the institutions park it in cash? Will they park it in commodities? Gold? Treasuries? The bond market still looks weak, particularly if the US is at risk of being unable to met their demands.

I remain very worried about the political crosshair aimed at the hedge funds and investment banks as I don't think the banks will be getting a bailout if they trade with depositors money and so if that is the rumor, they may have to stop using depositor money to borrow with. Not to mention if interest rates are rising all those who borrow money to speculate in stocks may have to liquidate and deleverage stocks and treasuries. The shift in that case would be into short term liquidity. If the euro elections are a result that creates fear of the euro's future, there could also be a shift into the swiss franc (for they no longer could maintain the "peg" to it and would have to sell euros... see when George Soros was accused of "breaking the bank"), as well as the dollar (the only market with large enough liquidity to accommodate the demand)

But if the shift is into the dollar, the balance sheets which have dolar denomonated assets will gain. There will be plenty of companies that sell to the US consumer but also have international interests that will gain. Even those based in other countries that are able to borrow in Yen or euros and do business in dollars but pay them back in euros or yen will do very well. Those companies could also act as a proxy for Europeans to get long the dollar without being a foreign exchange trader.

If you understand how the global markets really work, there are new opportunities that you may not have considered. If the elections perhaps pan out a different way, perhaps confidence will return into the euro and act as an area to hide from the US budgets. However, it is the euro that is structurally unsound and never going to be capable of being the reserve currency unless a central euro bond is made and individual country bonds are eliminated. All the bailouts that nations like Germany have done may end up "equalizing" the economies of europe and that may become economically viable at some point,but until then, there is too much incentive for countries to spend, promise nothing, and hope to get bailed out, and then because the rates are fixed to the euro, the yields will have to skyrocket in order for them to raise enough cash in euros. This creates tons of instability, and actually may be what triggers a lack of confidence in government debt around the world in the future. There have been bailouts, bail-ins, (selectively robbing large depositors via "taxes" that they never knew about when they made the deposits of cyprus) and austerity and taxation, you name it, they have tried it. Yet they find it so difficult to pay their obligations, and if they cut back on them, there are riots which kill tourism and economic growth. Eventually it will become too painful that abandoning the euro all together becomes a potential option. With even the threat/perception of that happening, there could be massive shifts of capital around the world.

Be wary of hype as those who have a vested interest in selling may pay for relatively small budgets and programs and funds to hype up the market so that they can get ou. If you see lots of hype, be the "smart money" and take the other side.

In this case, I think there is increased probability of a highly volatile move in major markets, but that it soon will sort itself out afterwards and provide tremendous opportunity. Due to the concerns of volatility, the retail investor may want to "reduce" position size of any area they are too exposed to.

Tuesday, July 30, 2013

analog trading

I had a long post on this but somehow it didn't save as it should have. This will be shorter than the original, but I still believe I have most of the initial images.

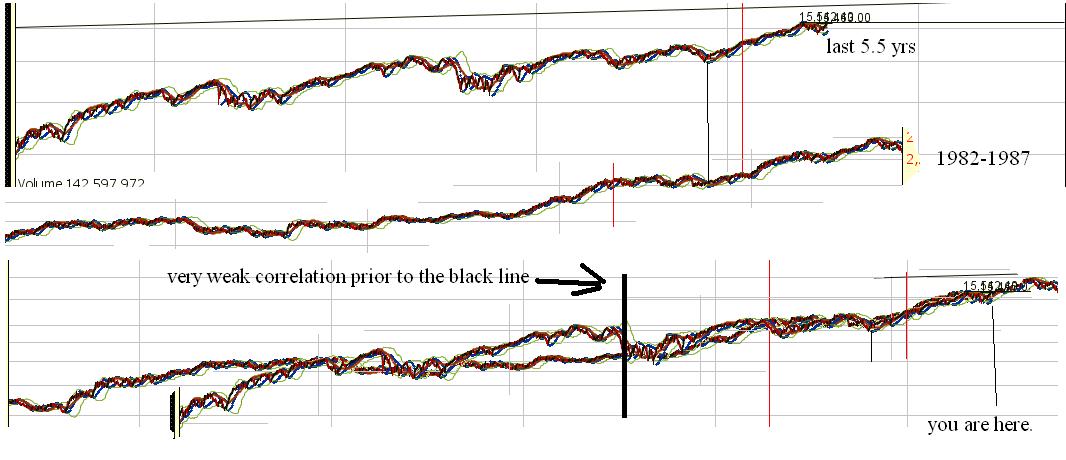

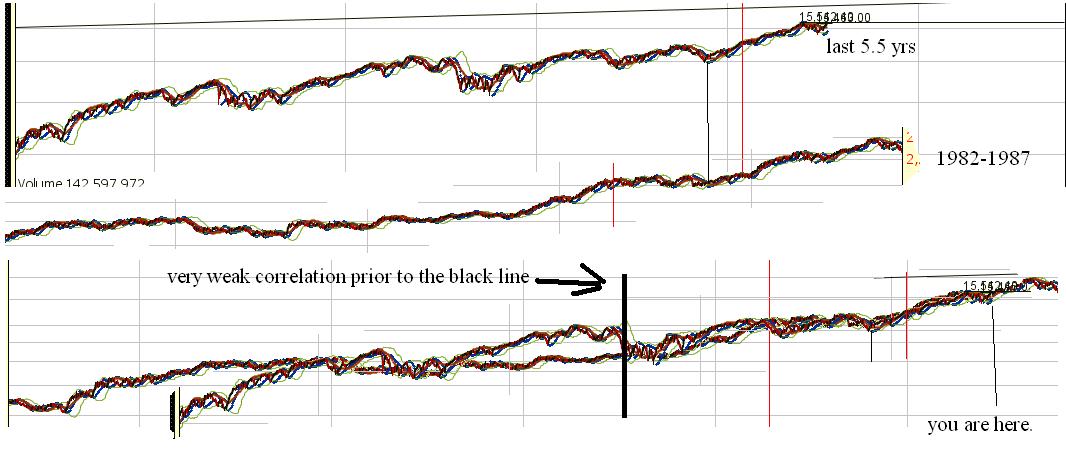

"Analogs" are basically using the past to see if the present matches up with it. If you use a 1987 analog, you are basically expecting the market to behave similarly to as it did back then. Analog trading requires some understanding of psychology and the events that occurred at the time. It requires an understanding of debt markets and what drives the particular settings. To trade via analogs, you first must identify the time periods that the market behaves similarly. Once you identify the past as similarly you go forward in the future looking for similar results.

Sometimes the charts will diverge, and either the trend will be broken, or else you could see a convergence of trends again. It often will be difficult to tell if the trend has just diverged, or if it permanantly broke the relationship. So you have to understand the fundamental nature of the market and determine if laws were passed anywhere in the world that may permanantly effect capital flows. Perhaps there is a crash that permanantly effects the flows of capital, or a break of suppor/resistance. Analog trading isn't enough on it's own, but can serve as a guideline.

Another thing you can do to use analog trading is look at "presidential cycle" and Seasonal data as well as the 10 year cycle and perhaps secular data (that averages beginning to end of each market cycle). Or you can take all analog's record the daily, weekly, or monthly prices open, close, high and low and line them up with the time period looks best and take the and average them together in excel or something, then plot them in a graph form next to the current "cycle". You can basically use the same method mentioned in the post that teaches you how to create your own seasonal charts. Only gathering historical data for a time period back to the 1900s may be difficult. you may have to do this manually.

At any rate, using this information may give you guidelines that help tune up your "market bias" and position your portfolio accordingly.

yearly chart

You can use this information to determine targets, maximum targets, average targets, upside vs downside targets and determine a "risk" vs reward, and based upon the number of analogs determine the amount that line up and estimate a probability of each event, and use it to manage risk and position yourself according to probability and edge, and provide extra cash for uncertainty.

You can apply this knowledge to combine it with other charts that perhaps look at earnings and future earnings estimates of the companies on average, historical PE averages and things of this nature to match the fundmental picture. You can also use technical analysis as well and combine all the information you can weighted by how valuable the analysis is or how accurate you beleive it to be.

The accuracy rate is important, but so is predictability and "sample size" and "confidence" that the particular indicator or method will provide you with reliable signals. Unfortunately, people using intuitive "confidence" tend to be optomistic at the wrong times, so unless you have a history of making judgements that can be proven statistically or past statistics, or have a strong reason to believe the stats will diverge, you probabl won't find a ton of value off just guessing.

Regardless, put "analog" trading into your arsenal. Depending on how we look after we get past September and perhaps October, or as early as mid August, I could potentially change my outlook to dramatically bullish or bearish. We could line up with the 1987 crash soon, and September has the budget ceiling and elections in Germany that creates risk.

"Analogs" are basically using the past to see if the present matches up with it. If you use a 1987 analog, you are basically expecting the market to behave similarly to as it did back then. Analog trading requires some understanding of psychology and the events that occurred at the time. It requires an understanding of debt markets and what drives the particular settings. To trade via analogs, you first must identify the time periods that the market behaves similarly. Once you identify the past as similarly you go forward in the future looking for similar results.

Sometimes the charts will diverge, and either the trend will be broken, or else you could see a convergence of trends again. It often will be difficult to tell if the trend has just diverged, or if it permanantly broke the relationship. So you have to understand the fundamental nature of the market and determine if laws were passed anywhere in the world that may permanantly effect capital flows. Perhaps there is a crash that permanantly effects the flows of capital, or a break of suppor/resistance. Analog trading isn't enough on it's own, but can serve as a guideline.

Another thing you can do to use analog trading is look at "presidential cycle" and Seasonal data as well as the 10 year cycle and perhaps secular data (that averages beginning to end of each market cycle). Or you can take all analog's record the daily, weekly, or monthly prices open, close, high and low and line them up with the time period looks best and take the and average them together in excel or something, then plot them in a graph form next to the current "cycle". You can basically use the same method mentioned in the post that teaches you how to create your own seasonal charts. Only gathering historical data for a time period back to the 1900s may be difficult. you may have to do this manually.

At any rate, using this information may give you guidelines that help tune up your "market bias" and position your portfolio accordingly.

yearly chart

You can use this information to determine targets, maximum targets, average targets, upside vs downside targets and determine a "risk" vs reward, and based upon the number of analogs determine the amount that line up and estimate a probability of each event, and use it to manage risk and position yourself according to probability and edge, and provide extra cash for uncertainty.

You can apply this knowledge to combine it with other charts that perhaps look at earnings and future earnings estimates of the companies on average, historical PE averages and things of this nature to match the fundmental picture. You can also use technical analysis as well and combine all the information you can weighted by how valuable the analysis is or how accurate you beleive it to be.

The accuracy rate is important, but so is predictability and "sample size" and "confidence" that the particular indicator or method will provide you with reliable signals. Unfortunately, people using intuitive "confidence" tend to be optomistic at the wrong times, so unless you have a history of making judgements that can be proven statistically or past statistics, or have a strong reason to believe the stats will diverge, you probabl won't find a ton of value off just guessing.

Regardless, put "analog" trading into your arsenal. Depending on how we look after we get past September and perhaps October, or as early as mid August, I could potentially change my outlook to dramatically bullish or bearish. We could line up with the 1987 crash soon, and September has the budget ceiling and elections in Germany that creates risk.

A System Of Systems

Trading systems are great and all, however even the best systems have periods in the cycle where they are less likely to be successful. At least, there are periods in time when those systems may benefit from having a hedge by another system. The hedge will reduce your correlation and in effect increase your exposure to the market when times are good (by hedging less) and decrease the correlation or exposure to market's movement when the market is more vulnerable.

Basically I follow the sentiment chart, which is not so much of a system on it's own.

I follow the risk cycle which also isn't it's system on it's own.

But I can choose between successful systems and this allows me to get the correlation I want and the risk I want.

SO let's break it down....

So focus on what works well within the sentiment chart, but also remember the "risk cycle"...

The risk cycle shifts from quality to growth to momentum to short squeezes to "trash" to "lotto", to correction (shorts) and back to quality again). You will go through this cycle several times over the sentiment chart on a weekly chart and daily chart, but the cycle itself works on a 30m basis or even 15m and in that case one "cycle" from quality and on back to quality again may actually look quite similar to this chart on some timeframe. In other words after Panic, you may trade quality and again at discouragment. Then the equal high and pullback you begin to look at growth. Then momentum after that low holds and as the equal highs are broken. Then it chops and offers some confusing signals during the "anxiety and wall of worry" phase. Quality still does well here, but after Aversion it's the growth and momentum that take off, and after denial everything works great, particularly the short squeeze. The trash works in the returning confidence and euphoria phrases and then the hedges work well at the top of returning confidence and euphoria phase. Then the panic low and hedges should be taken off or reduced and closed after the first low after the equal high during discouragement phase.

The markets can have multiple interpretation of some of these signals and it won't always work out as you expect, but they serve as a guideline. You could have a second wave down of panic when you thought it was just aversion or discouragement. But the other problem is the longer timeframe chart usually rules the day. This can cause some short term 30m charts to fail when the daily is setting up a certain phase but the weekly buyers are in another phase and even the daily which just messed up the 15m or 30m chart now interferes. This is what makes the chart a bit challenging but it does serve as a great guideline to anticipate and the sentiment chart goes along well with the risk cycle.

In terms of systems, you should always have one that makes sense with the given environment. You wouldn't want to trade high tight flags aggressively through the panic phases without a hedge even though they do tend to work even in bear markets. You wouldn't want to start hedging after aversion or denial phases even though the hedging strategy is profitable in bull markets. That doesn't mean you pass up the good setups and go fullly exposed long just because your interpretation of both the risk and sentiment cycle is hat you are bout to launch. Rather it means that you would have the fewest amount of hedges and require the setups to be much more ideal to take a hedge just before it goes higher, and you would take on MORE bullish trades. You shift allocations towards various strategy to favor the environment you suspect will occur.

For example, You might have a simple version of this where you only trade the high tight flag system and the bearish candlestick patterns as hedges. You have a decision to make on whether you want to shift between mostly cash and high tight flags, with the occasional hedge, or if you are willing to swing entirely bearish when the time is right or somewhere between. Generally history favors those with at least some kind of bullish bias, so you might say the maximum amount of high tight flags you have on is 10, but the maximum bearish candlestick bets you will hve on at once is 8. The total maximum trades you might have on might be 12.

These aren't number determined by random guesses, but instead should be scientifically calculated based upon risk. That means you probably will want a kelly criterion calculator adjusted for fees like the one I have discussed before to determine maximum number of trades at once as well as given the strategy. The difference is only correlation and expectation that determines why you might have 12 total trades even though you are limited to only 10 high tight flags. The ratio of long to short may depend upon your skill and ability as well as your comfort level with the risks of being bearish.

I believe you want a master checklist to run the systems so that you can follow it as intended when perhaps your emotions may be more inclined to take over. The master checklist may refer to individual checklists to run individual systems.

Basically I follow the sentiment chart, which is not so much of a system on it's own.

I follow the risk cycle which also isn't it's system on it's own.

But I can choose between successful systems and this allows me to get the correlation I want and the risk I want.

SO let's break it down....

So focus on what works well within the sentiment chart, but also remember the "risk cycle"...

The risk cycle shifts from quality to growth to momentum to short squeezes to "trash" to "lotto", to correction (shorts) and back to quality again). You will go through this cycle several times over the sentiment chart on a weekly chart and daily chart, but the cycle itself works on a 30m basis or even 15m and in that case one "cycle" from quality and on back to quality again may actually look quite similar to this chart on some timeframe. In other words after Panic, you may trade quality and again at discouragment. Then the equal high and pullback you begin to look at growth. Then momentum after that low holds and as the equal highs are broken. Then it chops and offers some confusing signals during the "anxiety and wall of worry" phase. Quality still does well here, but after Aversion it's the growth and momentum that take off, and after denial everything works great, particularly the short squeeze. The trash works in the returning confidence and euphoria phrases and then the hedges work well at the top of returning confidence and euphoria phase. Then the panic low and hedges should be taken off or reduced and closed after the first low after the equal high during discouragement phase.

The markets can have multiple interpretation of some of these signals and it won't always work out as you expect, but they serve as a guideline. You could have a second wave down of panic when you thought it was just aversion or discouragement. But the other problem is the longer timeframe chart usually rules the day. This can cause some short term 30m charts to fail when the daily is setting up a certain phase but the weekly buyers are in another phase and even the daily which just messed up the 15m or 30m chart now interferes. This is what makes the chart a bit challenging but it does serve as a great guideline to anticipate and the sentiment chart goes along well with the risk cycle.

In terms of systems, you should always have one that makes sense with the given environment. You wouldn't want to trade high tight flags aggressively through the panic phases without a hedge even though they do tend to work even in bear markets. You wouldn't want to start hedging after aversion or denial phases even though the hedging strategy is profitable in bull markets. That doesn't mean you pass up the good setups and go fullly exposed long just because your interpretation of both the risk and sentiment cycle is hat you are bout to launch. Rather it means that you would have the fewest amount of hedges and require the setups to be much more ideal to take a hedge just before it goes higher, and you would take on MORE bullish trades. You shift allocations towards various strategy to favor the environment you suspect will occur.

For example, You might have a simple version of this where you only trade the high tight flag system and the bearish candlestick patterns as hedges. You have a decision to make on whether you want to shift between mostly cash and high tight flags, with the occasional hedge, or if you are willing to swing entirely bearish when the time is right or somewhere between. Generally history favors those with at least some kind of bullish bias, so you might say the maximum amount of high tight flags you have on is 10, but the maximum bearish candlestick bets you will hve on at once is 8. The total maximum trades you might have on might be 12.

These aren't number determined by random guesses, but instead should be scientifically calculated based upon risk. That means you probably will want a kelly criterion calculator adjusted for fees like the one I have discussed before to determine maximum number of trades at once as well as given the strategy. The difference is only correlation and expectation that determines why you might have 12 total trades even though you are limited to only 10 high tight flags. The ratio of long to short may depend upon your skill and ability as well as your comfort level with the risks of being bearish.

I believe you want a master checklist to run the systems so that you can follow it as intended when perhaps your emotions may be more inclined to take over. The master checklist may refer to individual checklists to run individual systems.

Sunday, July 28, 2013

Thursday, July 25, 2013

Protecting What You Got Part 2

In the first part of protecting what you got, we talked about establishing and growing a portfolio that is basically "emergency savings". Instead of actually saving that money in cash, I suggested saving it in a food ETF, gasoline ETF in addition to other potential "core" expenses. You will need some cash to protect you against say car breaking down or whatever in that fund, which is why I suggested a full year's worth. Perhaps even more. Additionally, people talk about getting your stuff "handled" via emergency fund BEFORE investing. I simply cut right to the chase and basically "invest" in a sense that costs probably go up over time, so that's also why you can put a little bit more. You basically put a year's worth of gasoline expenses into a gasoline ETF. You put a year's worth of FOOD expenses into a food or agricultural commodity ETF. You put a year's worth of everything else into the corresponding ETF. I might just take "miscellaneous" if it isn't a major expense or isn't likely to go up into a relatively stable high income investment right away that you can use from which to use the income towards what you may need. As time goes on, the income you collect grows your actual "cash" reserves.

What do you do after you've established a core that protects you in case of emergency? That insulates you from at least a year's worth of expenses regardless of what happens to prices of those expenses?

If you only have a very small amount, the fees and volatility of your portfolio will eat you up initially, So first, invest in "cash" until you have enough saved up. I would use a cash CD that pays interest or a "CD Ladder", then invest gradually in a dividend paying name. I don't like the risks of investing solely in ONE company, so I would use preferred shares ETF (PFF or PSK), or other high income such as HYG or corporate income CORP ETFs. Or perhaps even just the SPY or something similar that invests in the S&P.

Once your savings and capital grow, you probably want to build another income name, or continue to build a CD ladder as income comes in. It's good to get in the habit of creating the asset first, then using the interest payment from that asset to speculate. In other words, get a "CD Ladder". This is where you buy a 1 yr CD each month for 12 months and perhaps you put in whatever excess disposable income every month continuously, and then invest the principal plus interest into whatever areas you want, or start saving out of those to make the next investment. You then a year later have the income coming in each month, and from that capital you invest it while using your disposable income and putting that to replace the CD or whatever. This way if something happens and you need your normally "disposable/investable income", you still have that investing plan and have some time to adjust, and if your income grows you are still protecting the excess earnings first, and investing it second.

You earn money every month, you put that into a savings account, you build up that nest, you put it into a dividend account for higher yield. Then you go to work saving again, but now have some dividends from which to draw from in addition. The thing about dividend investing and long term investing is, if you have very little, you don't want to have a lot of transactions that cost you. Instead, you have capital being sold via dividends and transition into cash again and can build another position with the cash you accumulate without having to sell and then buy again.

After you have your core CD ladder, your income investment (dividend ETF), then I would start saving some liquid cash, and THEN once you match that cash, you invest half of it into dividend investments and/or long term trades. You then continue to save and repeat and then add some bonds and then some short term trades, then you add some currency trades and then a stock index, then some commodities, and some short term trades.

If you already have saved all the capital to invest, I would do something like this. If you don't, you progress your account to eventually develop towards this, with the idea in mind that you start out with a "riskless investment" (such as CD), followed by one that has some risk, but you basically progress from the least risky investments to the more risky as you alternate from riskless (CD) to risk (long term dividend paying investments). This way your account is built with stability first and so that you eventually have enough where fees aren't an issue so that you can actually make "shorter term trades" in the account.

As a non leveraged investor you do something like this.

10% investments (dividend paying, hold "forever" type of "Buffett" names)

10% long term trades

10% short term trades

10% bonds

10% commodities

10% Stock index

10% currency

10% liquid cash

10% illiquid income paying cash (CDs)

10% income

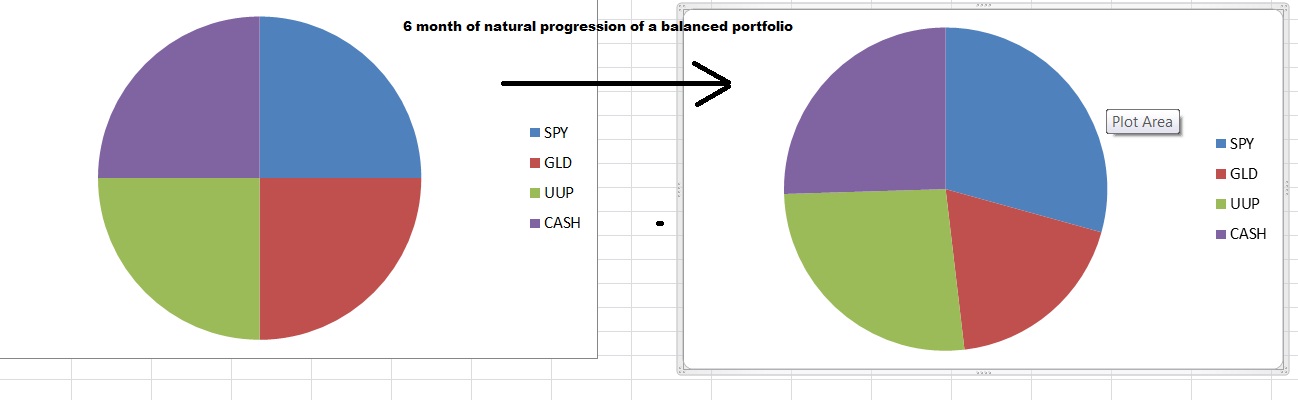

The strategy will be explained in more detail later. For now look at it. You really have 40% exposure to the stock market through trades, investments, indices. You have 40% exposure to cash via bonds, currency, liquid cash, cash CDs. Then you have 10% income which provides stability through capital flowing into account regularly. You have 10% commodities which can go up in a "risk on" type of environment, but also will help protect against price inflation that could potentially hurt some companies and slow long term growth. The portfolio is really "balanced" and really protects around half of your capital.

This strategy certainly has room for some shifting around. What you should be looking for is your "bias", and shift accordingly, but not too much. This is roughly a 50/50 strategy meaning it should be your allocation if you have no determined bias or think market has 50% chance of going up or down. If you think it has a 60%/40% you might have more trades, investments, and into a stock index. Perhaps there is one currency trade you really believe in for the long term and put more into it.

If you are a leverage investor seeking aggressive growth and speculation:

17.25% Non Leveraged Income (PFF,CORP,HYG,TLT)

4% Commodities LEAPS

4% stock indices LEAPS

4% currency bets LEAPS

10% hedging/cash for hedging

25% liquid cash for rebalancing

20% cash CD

2% highly leveraged short term plays "lottos"

11% 4 "core positions" long term. 2.75% each (position trades and investments using LEAPS options as stock replacement)

2.75% 2 half positions " non core" 1.375% each (swing trades and position trades using 3 month out options as stock replacements)

Even if you are aggressively leveraged, notice how you still have a very important goal of protecting yourself. To paraphrase SPDR... I mean the movie Spider Man, "With great [leverage], comes great responsibilities". Since you are using more leverage for the allocation/rebalancing area than other strategies, you need more cash for rebalancing, but you also need more cash to protect yourself from making mistakes especially since you have less income coming in. Since you have more core positions and half positions, you also need more cash and/or hedges in case those core positions and half positions grow to unhealthy levels since you don't want to be forced to sell them.

The goal of putting so much cash in a CD, cash, hedging, income, etc is not a return on investment, but a return OF investment. You are protecting yourself from going nuts and wanting to invest all the capital you have, as 20% is tied up in a cash CD, 17.25% is tied up in income, and then you tie up 12% capital in stock indices and currency LEAPS and commodity LEAPs which work together along with your cash and income to produce a very low correlation with the market overall, but still produce a return, and tie up capital that you won't be tempted to use elsewhere. If you are tempted to use excess capital you can use your hedging capital to hedge for every additional position if you must, but that is not the intention. Even your "core" positions and half positions protect a decent amount of capital as you buy much more time on the contract than they are worth, and you still leave some room for some highly leveraged short term plays or "lotto".

Once you really grow your account and produce enough income, you might put more capital to "lotto" trades, but this portfolio is already really aggressive.

Moderate leveraged investor

15% Non Leveraged Income (PFF,CORP,HYG,TLT)

10% long term individual DRIP/dividend investments

3% Commodities LEAPS

3% stock indices LEAPS

3% currency bets LEAPS

3% treasury bonds

5% hedging/cash for hedging

17% liquid cash for rebalancing

30% cash CD

1% highly leveraged short term plays "lottos"

8% 4 "core positions" long term. 2% each (position trades and investments using LEAPS options as stock replacement)

2% 2 half positions " non core" 1% each (swing trades and position trades using 3 month out options as stock replacements)

Conservative leveraged investor

35% Income

22% DRIP/dividends

2% commodities

2% stock indicies

2% currency bets

4% treasury bonds

2% hedging/cash for hedging

10% liquid cash for rebalancing

15% cash CD

3% 2 core positions of 1.5%

3% 4 half positions of .75%

As a conservative leveraged investor, you are using leverage to reduce risk and replace stock with options. In other words, if you were to buy 100 shares of stock, you would buy 1 call. The capital freed up allows for dividends investment. Because you have so much more tied up into dividend investments, there is less of a need to have cash. The cash will come in through dividends when you need it mostly. You will use less on your allocation models, and thus need less liquid cash for rebalancing. You will use smaller amounts on your allocation models, because your core and half positions will be smaller, and as a result, you need less cash for hedging those positions. Since you have smaller positions, you don't need as much cash and as a result, you have lots of cash, but since you aren't using those in more positions, you should be putting them in safe and stable income and dividend income.

Really, depending on your skill you might structure this differently. Perhaps your skill areas are in currencies and commodities, and would put more capital there instead of building core leveraged positions that you aren't skilled enough to use. If your skill is dividend income, perhaps you would be more drawn to the conservative strategy naturally. so it all really depends. Also, the market may dictate slightly different allocations. If commodities are cheap, oversold, and ready to go higher, you may put a more aggressive allocation towards them. Perhaps you trade very short term in currency and thus have a very low correlation with all your other accounts and can put more towards it and still trade it successfully with ability to maintain that balance by taking capital out and distributing it among other positions.

More on this later

What do you do after you've established a core that protects you in case of emergency? That insulates you from at least a year's worth of expenses regardless of what happens to prices of those expenses?

If you only have a very small amount, the fees and volatility of your portfolio will eat you up initially, So first, invest in "cash" until you have enough saved up. I would use a cash CD that pays interest or a "CD Ladder", then invest gradually in a dividend paying name. I don't like the risks of investing solely in ONE company, so I would use preferred shares ETF (PFF or PSK), or other high income such as HYG or corporate income CORP ETFs. Or perhaps even just the SPY or something similar that invests in the S&P.

Once your savings and capital grow, you probably want to build another income name, or continue to build a CD ladder as income comes in. It's good to get in the habit of creating the asset first, then using the interest payment from that asset to speculate. In other words, get a "CD Ladder". This is where you buy a 1 yr CD each month for 12 months and perhaps you put in whatever excess disposable income every month continuously, and then invest the principal plus interest into whatever areas you want, or start saving out of those to make the next investment. You then a year later have the income coming in each month, and from that capital you invest it while using your disposable income and putting that to replace the CD or whatever. This way if something happens and you need your normally "disposable/investable income", you still have that investing plan and have some time to adjust, and if your income grows you are still protecting the excess earnings first, and investing it second.

You earn money every month, you put that into a savings account, you build up that nest, you put it into a dividend account for higher yield. Then you go to work saving again, but now have some dividends from which to draw from in addition. The thing about dividend investing and long term investing is, if you have very little, you don't want to have a lot of transactions that cost you. Instead, you have capital being sold via dividends and transition into cash again and can build another position with the cash you accumulate without having to sell and then buy again.

After you have your core CD ladder, your income investment (dividend ETF), then I would start saving some liquid cash, and THEN once you match that cash, you invest half of it into dividend investments and/or long term trades. You then continue to save and repeat and then add some bonds and then some short term trades, then you add some currency trades and then a stock index, then some commodities, and some short term trades.

If you already have saved all the capital to invest, I would do something like this. If you don't, you progress your account to eventually develop towards this, with the idea in mind that you start out with a "riskless investment" (such as CD), followed by one that has some risk, but you basically progress from the least risky investments to the more risky as you alternate from riskless (CD) to risk (long term dividend paying investments). This way your account is built with stability first and so that you eventually have enough where fees aren't an issue so that you can actually make "shorter term trades" in the account.

As a non leveraged investor you do something like this.

10% investments (dividend paying, hold "forever" type of "Buffett" names)

10% long term trades

10% short term trades

10% bonds

10% commodities

10% Stock index

10% currency

10% liquid cash

10% illiquid income paying cash (CDs)

10% income

The strategy will be explained in more detail later. For now look at it. You really have 40% exposure to the stock market through trades, investments, indices. You have 40% exposure to cash via bonds, currency, liquid cash, cash CDs. Then you have 10% income which provides stability through capital flowing into account regularly. You have 10% commodities which can go up in a "risk on" type of environment, but also will help protect against price inflation that could potentially hurt some companies and slow long term growth. The portfolio is really "balanced" and really protects around half of your capital.

This strategy certainly has room for some shifting around. What you should be looking for is your "bias", and shift accordingly, but not too much. This is roughly a 50/50 strategy meaning it should be your allocation if you have no determined bias or think market has 50% chance of going up or down. If you think it has a 60%/40% you might have more trades, investments, and into a stock index. Perhaps there is one currency trade you really believe in for the long term and put more into it.

If you are a leverage investor seeking aggressive growth and speculation:

17.25% Non Leveraged Income (PFF,CORP,HYG,TLT)

4% Commodities LEAPS

4% stock indices LEAPS

4% currency bets LEAPS

10% hedging/cash for hedging

25% liquid cash for rebalancing

20% cash CD

2% highly leveraged short term plays "lottos"

11% 4 "core positions" long term. 2.75% each (position trades and investments using LEAPS options as stock replacement)

2.75% 2 half positions " non core" 1.375% each (swing trades and position trades using 3 month out options as stock replacements)

Even if you are aggressively leveraged, notice how you still have a very important goal of protecting yourself. To paraphrase SPDR... I mean the movie Spider Man, "With great [leverage], comes great responsibilities". Since you are using more leverage for the allocation/rebalancing area than other strategies, you need more cash for rebalancing, but you also need more cash to protect yourself from making mistakes especially since you have less income coming in. Since you have more core positions and half positions, you also need more cash and/or hedges in case those core positions and half positions grow to unhealthy levels since you don't want to be forced to sell them.

The goal of putting so much cash in a CD, cash, hedging, income, etc is not a return on investment, but a return OF investment. You are protecting yourself from going nuts and wanting to invest all the capital you have, as 20% is tied up in a cash CD, 17.25% is tied up in income, and then you tie up 12% capital in stock indices and currency LEAPS and commodity LEAPs which work together along with your cash and income to produce a very low correlation with the market overall, but still produce a return, and tie up capital that you won't be tempted to use elsewhere. If you are tempted to use excess capital you can use your hedging capital to hedge for every additional position if you must, but that is not the intention. Even your "core" positions and half positions protect a decent amount of capital as you buy much more time on the contract than they are worth, and you still leave some room for some highly leveraged short term plays or "lotto".

Once you really grow your account and produce enough income, you might put more capital to "lotto" trades, but this portfolio is already really aggressive.

Moderate leveraged investor

15% Non Leveraged Income (PFF,CORP,HYG,TLT)

10% long term individual DRIP/dividend investments

3% Commodities LEAPS

3% stock indices LEAPS

3% currency bets LEAPS

3% treasury bonds

5% hedging/cash for hedging

17% liquid cash for rebalancing

30% cash CD

1% highly leveraged short term plays "lottos"

8% 4 "core positions" long term. 2% each (position trades and investments using LEAPS options as stock replacement)

2% 2 half positions " non core" 1% each (swing trades and position trades using 3 month out options as stock replacements)

Conservative leveraged investor

35% Income

22% DRIP/dividends

2% commodities

2% stock indicies

2% currency bets

4% treasury bonds

2% hedging/cash for hedging

10% liquid cash for rebalancing

15% cash CD

3% 2 core positions of 1.5%

3% 4 half positions of .75%

As a conservative leveraged investor, you are using leverage to reduce risk and replace stock with options. In other words, if you were to buy 100 shares of stock, you would buy 1 call. The capital freed up allows for dividends investment. Because you have so much more tied up into dividend investments, there is less of a need to have cash. The cash will come in through dividends when you need it mostly. You will use less on your allocation models, and thus need less liquid cash for rebalancing. You will use smaller amounts on your allocation models, because your core and half positions will be smaller, and as a result, you need less cash for hedging those positions. Since you have smaller positions, you don't need as much cash and as a result, you have lots of cash, but since you aren't using those in more positions, you should be putting them in safe and stable income and dividend income.

Really, depending on your skill you might structure this differently. Perhaps your skill areas are in currencies and commodities, and would put more capital there instead of building core leveraged positions that you aren't skilled enough to use. If your skill is dividend income, perhaps you would be more drawn to the conservative strategy naturally. so it all really depends. Also, the market may dictate slightly different allocations. If commodities are cheap, oversold, and ready to go higher, you may put a more aggressive allocation towards them. Perhaps you trade very short term in currency and thus have a very low correlation with all your other accounts and can put more towards it and still trade it successfully with ability to maintain that balance by taking capital out and distributing it among other positions.

Protecting What You Got Part 1

I believe far too much emphasis has been placed in maximizing gains, we first need to backtrack and decide how are we going to protect what we got? There are too many people that can't sleep at night because they didn't protect what they have.

Many people live paycheck to paycheck. What if gasoline prices double, could you still pay your bills? What if it multiplied by 10? Everyone has a point, no matter how extreme where they can be broken financially, the goal is to reduce or eliminate all perceived risks that one can think of.

So you may have an account dedicated towards hedging. You may buy a UGA fund (gasoline), a DBA or FUD fund (food), you may buy an income fund that eventually will grow to handle your expenses and also hedge against risks of government tax increases to pay the bond holders (municipal and treasuries), or bet against treasury if you have a fixed rate mortgage.

You may have a fund that bets on both the dollar (UUP) and perhaps another currency in case the demand shifts.

If these match your annual expense, and you cannot meet obligations one month, you can withdraw 1/12th of it to pay for expenses. The goal is to have multiple years worth of insulation from risks, and you may even benefit if the expenses of living go up.

That's one way to protect your interests. Perhaps you own a house? If so, and the equity has skyrocketed like it did in 2007, you might refinance and take out a huge loan get mortgage to the gills and put that money into treasuries. Now if the price of home tumbles, you have locked in a high interest rate and if the government lowers interest rates to try to get things moving you will have a very high principal and be able to pay off your home. The interest coming in will help you make good on your house payments and you can think about refinancing at a lower interest rate in the future. Technically you might owe more than the house is worth, but because you protected yourself from a decline, you have insulated yourself from the damages.

But that's only one area "hedging daily expenses" that needs to be handled. Some people advise to save in cash 6 months of expenses. If I were certified to, I would advise to have a year saved in CORE expenses saved in ETFs that will increase if those expense increase first, and to be withdrawn only in the event of an emergency.

What you do after you build the core "protection" strategy is complicated and will be covered in detail in the next post of protecting what you got.

Many people live paycheck to paycheck. What if gasoline prices double, could you still pay your bills? What if it multiplied by 10? Everyone has a point, no matter how extreme where they can be broken financially, the goal is to reduce or eliminate all perceived risks that one can think of.

So you may have an account dedicated towards hedging. You may buy a UGA fund (gasoline), a DBA or FUD fund (food), you may buy an income fund that eventually will grow to handle your expenses and also hedge against risks of government tax increases to pay the bond holders (municipal and treasuries), or bet against treasury if you have a fixed rate mortgage.

You may have a fund that bets on both the dollar (UUP) and perhaps another currency in case the demand shifts.

If these match your annual expense, and you cannot meet obligations one month, you can withdraw 1/12th of it to pay for expenses. The goal is to have multiple years worth of insulation from risks, and you may even benefit if the expenses of living go up.

That's one way to protect your interests. Perhaps you own a house? If so, and the equity has skyrocketed like it did in 2007, you might refinance and take out a huge loan get mortgage to the gills and put that money into treasuries. Now if the price of home tumbles, you have locked in a high interest rate and if the government lowers interest rates to try to get things moving you will have a very high principal and be able to pay off your home. The interest coming in will help you make good on your house payments and you can think about refinancing at a lower interest rate in the future. Technically you might owe more than the house is worth, but because you protected yourself from a decline, you have insulated yourself from the damages.

But that's only one area "hedging daily expenses" that needs to be handled. Some people advise to save in cash 6 months of expenses. If I were certified to, I would advise to have a year saved in CORE expenses saved in ETFs that will increase if those expense increase first, and to be withdrawn only in the event of an emergency.

What you do after you build the core "protection" strategy is complicated and will be covered in detail in the next post of protecting what you got.

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

How The Economy Works (Domestic View)

In the post The Giant Flow Chart of Capital, I discussed briefly how money is always exchanging hands. I am going to attempt today to describe the more complex market of how it works.

The Central Banks create money, (in the US they call it the federal reserve). The government issues them bonds, and may also extend credit through a tax credit or government grants (such as student loans) to individuals and companies. The governments create public debt which they owe and must pay off, and do so through taxes. The private banks also borrow from the central bank and then issue the credit to individuals and corporations for a higher interest rate than what they borrow at. The individuals and corporations then put money into the economy by paying whoever it is they got the loan to buy. Commonly they will either go into credit card debt to pay for things like gasoline or to go shopping, or they will go into debt to buy a house. The person collecting the money who is selling there house will probably pay off existing debt, and possibly if any is left over deposit money into the bank. The banks typically have some sort of "reserve" that is perhaps 10% of the money loaned out. In other words, for every $1 in deposits the bank has, it has lent out $10. With every loan come more deposits, and with every deposit comes the ability to create more loans. Before the financial crisis of 2008, banks like Lehman Brothers were leveraged 40 to 1 meaning for every $1, it lent out $40. One might think that this is inflationary because of all the money it creates in the system.

However, you must also understand that for every $40 lent out,over the course of the loan at a rate of perhaps 5% per year, over 30 years the borrower will pay nearly twice that at $77.30.

So with leverage comes lots of risk. On one hand you have lots of money in the system as leverage expands. On the other hand, if you don't have new money being created as prior debt obligations come due, not everyone will be able to make the payments. The system requires inflation of the monetary supply, or delinquent payments, default and foreclosure. The 2008 crisis was bad because of the housing bubble created prior to 2008. When a few people start to default and confidence in real estate exists at all time highs and you are unable to sustain that speculation (which will ultimately happen), you suddenly have not as many people who want to buy, and it doesn't take many that want to sell. On top of that you have banks foreclosing and listing properties at 25% of the market value, and soon everyone else has to reduce their price since there isn't enough buying demand, and those still in a home soon see that driving down price, they then end up owing more money then their house is worth, and then they might walk away or stop making good on their payments and foreclosure occurs again, and the bank must liquidate more properties. Since so many jobs are leveraged to real estate and leveraged to easy credit in the system, it's very difficult to get the confidence going again and that is why the 2008 crisis lead to systemic risk. It certainly wasn't the only reason, but that ishow capital markets work.

To try to counteract these effects, the government really expanded, spending a lot more, and going into deficit spending. In the processes, now they went into debt, created a lot of government jobs to try to counteract the job losses and get the economy moving again. The problem with that is rather than just borrow to pay for it and grow the economy, this actually has limited growth. The government was consuming the job demand. While even though the dollar during the peak of the crisis may have been worth about 50% more than it's low point, the debts still had to be paid in dollars, not what they were worth. Salaries and the amount companies were supposed to pay employees had to be paid in dollars.

business activity slowed and companies had debts to pay and couldn't make payroll. There wasn't enough money around to sustain the previous levels of activity. The companies could not make payments because goods and services were bought when the dollar was low, inventories were high. People were laid off in 2008 because they owed everyone money in dollars which now had increased 50%. Since the debts were not adjusted lower 50% to keep them in line at an equal value with what they were lent out at, and because the payments to employees were not cut in half, the companies had to cut them in half another way... Through firing people. Of course this accelerated the decline because that mean less income available for the economy. If instead you made the banks cut their payments and principal corresponding to the strength of the dollar, it may have made a different impact. However, the dollar was very volatile and the federal reserve lowered interest rates and injected money into the system and bailed out the banks.

See a debt crisis that only Julius Caesar Understood.

The government instead capitalized by seizing more control in a power grab. They kept the payroll tax which means that the businesses have to pay money for hiring employees aside from what they pay the employees creating a burden much greater. The government went into deficit spending and had the public sector displace the loss in jobs by the private sector. Instead if they cut the debts owned by individuals and corporations even partially, it would have made things easier on corporations to produce more, charge less, and employ more people and restore confidence and sustain the real estate prices without creating such a shock to the system.

Instead the government with it's "unlimited" budget, forced corporations to compete with the government wage scale (while the government doesn't have to pay a payroll tax, if it did, it would be to itself anyways) in a time when the dollar was in massive demand and during a consumer confidence shock. As a result, the easiest option for businesses was to only keep overseas employees and cut American salaries and wages where possible. Those consumers the government hires may be able to go out and spend on the economy, but at what cost? Taking away money from those who produce in the economy and innovate and find ways of providing cheaper and cheaper goods and to do more and more with less and less through innovation. That requires MORE businesses competing with each other in the business/private sector, rather than the government grabbing greater control and a larger share of the job market, and the large, politically connected businesses only to survive without having to do as much. The big government supporters fail to realize that this type of action of growing government just reinforces the negative aspects of a monopoly. In a corporate boom, a monopoly is only possible if a company finds completely new ways of delivering at prices consumers are willing to pay, rather than growing through political power and influence and using the politicians to make it tougher on new start up businesses that could otherwise create jobs.

I'm not hypocritical of the government hiring and doing what it needs to do in a crisis, just the current paradigm of economics not taking into account that post bretton woods there was the closing of the gold window and debt is just another currency that just happens to pay interest. I certainly think the bailouts and stimulous were more benneficial to the economy for the time being than if they hadn't. I just think that we passed on some of the burden down the road, and there's a real failure to understand how borrowing money is very costly. The government's deficit spending has not raised the amount of private productivity and profit overall, and they can't tax business enough to pay all their debt obligations. Nevermind if the dollar continues it's bull market with government debt already so high and GDP stagnant. Nevermind what will happen to debt if interest rates skyrocket. (it will go up when the debt is rolled over to the new interest rates)

What's worse, is STATE governments actually cannot expand the money supply like the fed and now state governments are likely going to be forced to cut back like Detroit did. I don't believe the problem was stopped, it was only shifted and delayed.

This is the wage environment in 1900 vs 1980

Agriculture is a small small portion of the economy because of the invention of modern farming. However, the service industry and manufacturing bases most likely shrunk in share in 2008 as the government grew in size. That won't last. The government has been shrinking and unemployment has been rising and is still in an uptrend since it's low in 2000, even if it may be declining from the spike high depending upon if you count people "out of work" but not collecting benefits as unemployed (the government does not).

Unemployment is rising from the public sector.

As people were laid off, they had less money to spend and pay for the products and services. This was a huge problem. But cutting the amount owed would have created a boom immediately and all at once, hurting savers, but providing them with much higher interest rates than they would have had if they solved it by having the fed burn up a portion of it's bonds that the government owes it, eliminating some of the debt burden on the government, and injecting unbacked excess cash into the system that was so in demand. The government wouldn't have to raise the debt ceiling as they did, and yet they could spend what they wanted to. The private sector would get their bailout through reducing the mortgage cost. The boom created would be an inflationary one that wouldn't do so in a way that created huge costs, and instead would reduce the costs causing it to be good for america. The ramifications are still complicated, but you could stop the deteriorating confidence while also creating a very strong shift in economic power to the government, which historically has severe long term conseqences.

The domestic view is still complicated, capital rotates around the different areas in the US. In theory rising interest rates is bad for the economy because it means the costs to borrow are higher. In theory lower interest rates are good for the economy because more people borrow. But in reality people recognize the falling market, and understand that the cost to get a loan will be cheaper in the future since it is a falling interest rate environment. Economics 101, opportunity cost says that if it costs you $100 to save $50, it isn't a decision worth making. If it costs you $50 to save $100 it is. In this case, the cost is time, and giving up time by waiting to refinance and waiting to be a first time home-buyer, expects to yield savings on your annual interest rate payment, especially when home prices are also falling. Only when rates finally begin to rise do suddenly people recognize that the cost to WAIT become extremely expensive.

Theory is not reality, but we've only scratched the surface. The question is, are you willing to see how far down the rabbit hole really goes, Neo?

The Central Banks create money, (in the US they call it the federal reserve). The government issues them bonds, and may also extend credit through a tax credit or government grants (such as student loans) to individuals and companies. The governments create public debt which they owe and must pay off, and do so through taxes. The private banks also borrow from the central bank and then issue the credit to individuals and corporations for a higher interest rate than what they borrow at. The individuals and corporations then put money into the economy by paying whoever it is they got the loan to buy. Commonly they will either go into credit card debt to pay for things like gasoline or to go shopping, or they will go into debt to buy a house. The person collecting the money who is selling there house will probably pay off existing debt, and possibly if any is left over deposit money into the bank. The banks typically have some sort of "reserve" that is perhaps 10% of the money loaned out. In other words, for every $1 in deposits the bank has, it has lent out $10. With every loan come more deposits, and with every deposit comes the ability to create more loans. Before the financial crisis of 2008, banks like Lehman Brothers were leveraged 40 to 1 meaning for every $1, it lent out $40. One might think that this is inflationary because of all the money it creates in the system.

However, you must also understand that for every $40 lent out,over the course of the loan at a rate of perhaps 5% per year, over 30 years the borrower will pay nearly twice that at $77.30.

So with leverage comes lots of risk. On one hand you have lots of money in the system as leverage expands. On the other hand, if you don't have new money being created as prior debt obligations come due, not everyone will be able to make the payments. The system requires inflation of the monetary supply, or delinquent payments, default and foreclosure. The 2008 crisis was bad because of the housing bubble created prior to 2008. When a few people start to default and confidence in real estate exists at all time highs and you are unable to sustain that speculation (which will ultimately happen), you suddenly have not as many people who want to buy, and it doesn't take many that want to sell. On top of that you have banks foreclosing and listing properties at 25% of the market value, and soon everyone else has to reduce their price since there isn't enough buying demand, and those still in a home soon see that driving down price, they then end up owing more money then their house is worth, and then they might walk away or stop making good on their payments and foreclosure occurs again, and the bank must liquidate more properties. Since so many jobs are leveraged to real estate and leveraged to easy credit in the system, it's very difficult to get the confidence going again and that is why the 2008 crisis lead to systemic risk. It certainly wasn't the only reason, but that ishow capital markets work.

To try to counteract these effects, the government really expanded, spending a lot more, and going into deficit spending. In the processes, now they went into debt, created a lot of government jobs to try to counteract the job losses and get the economy moving again. The problem with that is rather than just borrow to pay for it and grow the economy, this actually has limited growth. The government was consuming the job demand. While even though the dollar during the peak of the crisis may have been worth about 50% more than it's low point, the debts still had to be paid in dollars, not what they were worth. Salaries and the amount companies were supposed to pay employees had to be paid in dollars.

business activity slowed and companies had debts to pay and couldn't make payroll. There wasn't enough money around to sustain the previous levels of activity. The companies could not make payments because goods and services were bought when the dollar was low, inventories were high. People were laid off in 2008 because they owed everyone money in dollars which now had increased 50%. Since the debts were not adjusted lower 50% to keep them in line at an equal value with what they were lent out at, and because the payments to employees were not cut in half, the companies had to cut them in half another way... Through firing people. Of course this accelerated the decline because that mean less income available for the economy. If instead you made the banks cut their payments and principal corresponding to the strength of the dollar, it may have made a different impact. However, the dollar was very volatile and the federal reserve lowered interest rates and injected money into the system and bailed out the banks.

See a debt crisis that only Julius Caesar Understood.

The government instead capitalized by seizing more control in a power grab. They kept the payroll tax which means that the businesses have to pay money for hiring employees aside from what they pay the employees creating a burden much greater. The government went into deficit spending and had the public sector displace the loss in jobs by the private sector. Instead if they cut the debts owned by individuals and corporations even partially, it would have made things easier on corporations to produce more, charge less, and employ more people and restore confidence and sustain the real estate prices without creating such a shock to the system.

Instead the government with it's "unlimited" budget, forced corporations to compete with the government wage scale (while the government doesn't have to pay a payroll tax, if it did, it would be to itself anyways) in a time when the dollar was in massive demand and during a consumer confidence shock. As a result, the easiest option for businesses was to only keep overseas employees and cut American salaries and wages where possible. Those consumers the government hires may be able to go out and spend on the economy, but at what cost? Taking away money from those who produce in the economy and innovate and find ways of providing cheaper and cheaper goods and to do more and more with less and less through innovation. That requires MORE businesses competing with each other in the business/private sector, rather than the government grabbing greater control and a larger share of the job market, and the large, politically connected businesses only to survive without having to do as much. The big government supporters fail to realize that this type of action of growing government just reinforces the negative aspects of a monopoly. In a corporate boom, a monopoly is only possible if a company finds completely new ways of delivering at prices consumers are willing to pay, rather than growing through political power and influence and using the politicians to make it tougher on new start up businesses that could otherwise create jobs.

I'm not hypocritical of the government hiring and doing what it needs to do in a crisis, just the current paradigm of economics not taking into account that post bretton woods there was the closing of the gold window and debt is just another currency that just happens to pay interest. I certainly think the bailouts and stimulous were more benneficial to the economy for the time being than if they hadn't. I just think that we passed on some of the burden down the road, and there's a real failure to understand how borrowing money is very costly. The government's deficit spending has not raised the amount of private productivity and profit overall, and they can't tax business enough to pay all their debt obligations. Nevermind if the dollar continues it's bull market with government debt already so high and GDP stagnant. Nevermind what will happen to debt if interest rates skyrocket. (it will go up when the debt is rolled over to the new interest rates)

What's worse, is STATE governments actually cannot expand the money supply like the fed and now state governments are likely going to be forced to cut back like Detroit did. I don't believe the problem was stopped, it was only shifted and delayed.

This is the wage environment in 1900 vs 1980

Agriculture is a small small portion of the economy because of the invention of modern farming. However, the service industry and manufacturing bases most likely shrunk in share in 2008 as the government grew in size. That won't last. The government has been shrinking and unemployment has been rising and is still in an uptrend since it's low in 2000, even if it may be declining from the spike high depending upon if you count people "out of work" but not collecting benefits as unemployed (the government does not).

Unemployment is rising from the public sector.

As people were laid off, they had less money to spend and pay for the products and services. This was a huge problem. But cutting the amount owed would have created a boom immediately and all at once, hurting savers, but providing them with much higher interest rates than they would have had if they solved it by having the fed burn up a portion of it's bonds that the government owes it, eliminating some of the debt burden on the government, and injecting unbacked excess cash into the system that was so in demand. The government wouldn't have to raise the debt ceiling as they did, and yet they could spend what they wanted to. The private sector would get their bailout through reducing the mortgage cost. The boom created would be an inflationary one that wouldn't do so in a way that created huge costs, and instead would reduce the costs causing it to be good for america. The ramifications are still complicated, but you could stop the deteriorating confidence while also creating a very strong shift in economic power to the government, which historically has severe long term conseqences.

The domestic view is still complicated, capital rotates around the different areas in the US. In theory rising interest rates is bad for the economy because it means the costs to borrow are higher. In theory lower interest rates are good for the economy because more people borrow. But in reality people recognize the falling market, and understand that the cost to get a loan will be cheaper in the future since it is a falling interest rate environment. Economics 101, opportunity cost says that if it costs you $100 to save $50, it isn't a decision worth making. If it costs you $50 to save $100 it is. In this case, the cost is time, and giving up time by waiting to refinance and waiting to be a first time home-buyer, expects to yield savings on your annual interest rate payment, especially when home prices are also falling. Only when rates finally begin to rise do suddenly people recognize that the cost to WAIT become extremely expensive.

Theory is not reality, but we've only scratched the surface. The question is, are you willing to see how far down the rabbit hole really goes, Neo?

Thursday, July 18, 2013

The Giant Flow Chart Of Capital

Paul Tudor Jones once said That the economies of the world and markets basically functioned liks a giant flow chart of capital"

Here is a very simplified version to explain the various shifts.

In this chart, you shift from cash and bond markets into commodity and stock/real estate markets when you have "inflation" and for the reason that people "risk adverse" and scared typically seek bonds and/or cash... And "risk on" as if bonds don't have risk (see the numerous defaults of sovereign and corporate debt throughout history) or cash (see defunct currencies that no longer are used in trade and have been replaced).

The type of inflation is either price inflation (commodity demand), or asset inflation (demand for assets like stocks and real estate and gold is really the wildcard). As such you can anticipate certain shifts in capital.

Then there is "deflation" or "risk off" trade where capital sells it's commodities and/or stocks. When both stocks and commodities sell off it usually is a crisis of confidence in risk and an aggressive shift to cash as DEBT is paid off, rather than expanded, growth slows or goes negative, and transactions and the velocity in which money moves slows down.

In the case of just a stock sell off with rising commodities we call it "stagflation" which usually is accompanied by low growth or "stagnation" and increased costs or "inflation".

In the case of commodity sell off while stocks go higher, we call this a "secular bull market", as prices cost less, usually leading to and accompanied by high growth.

What Paul Tudor Jones meant by the initial quote was capital can go to or from commodities, stocks, bonds and cash and back in any order depending on the condition. You could get much more specific and single out what stocks it will go to and so on, and to what extent and how much and try to narrow out why. The example used a small flow chart and really generalized. The real chart to map all capital movement would instead show how money is created from either governments or private banks THROUGH the king/queen/supreme leader/dictator/treasury department of the government, and/or the central bank depending on what point in history, how debt creates a promise to pay things back, how that promise results in a FUTURE obligation for capital to be paid off, and how because of interest, new debt must be created for all debt to be paid off and the system to keep going.

That's another story. For now just brainstorm and try to understand the "basic" rotations or "cycles" that occur because capital is shifting between the broad and basic major asset classes and the impact these shifts have and the things that cause them have.

Here is a very simplified version to explain the various shifts.

In this chart, you shift from cash and bond markets into commodity and stock/real estate markets when you have "inflation" and for the reason that people "risk adverse" and scared typically seek bonds and/or cash... And "risk on" as if bonds don't have risk (see the numerous defaults of sovereign and corporate debt throughout history) or cash (see defunct currencies that no longer are used in trade and have been replaced).

The type of inflation is either price inflation (commodity demand), or asset inflation (demand for assets like stocks and real estate and gold is really the wildcard). As such you can anticipate certain shifts in capital.

Then there is "deflation" or "risk off" trade where capital sells it's commodities and/or stocks. When both stocks and commodities sell off it usually is a crisis of confidence in risk and an aggressive shift to cash as DEBT is paid off, rather than expanded, growth slows or goes negative, and transactions and the velocity in which money moves slows down.

In the case of just a stock sell off with rising commodities we call it "stagflation" which usually is accompanied by low growth or "stagnation" and increased costs or "inflation".

In the case of commodity sell off while stocks go higher, we call this a "secular bull market", as prices cost less, usually leading to and accompanied by high growth.

What Paul Tudor Jones meant by the initial quote was capital can go to or from commodities, stocks, bonds and cash and back in any order depending on the condition. You could get much more specific and single out what stocks it will go to and so on, and to what extent and how much and try to narrow out why. The example used a small flow chart and really generalized. The real chart to map all capital movement would instead show how money is created from either governments or private banks THROUGH the king/queen/supreme leader/dictator/treasury department of the government, and/or the central bank depending on what point in history, how debt creates a promise to pay things back, how that promise results in a FUTURE obligation for capital to be paid off, and how because of interest, new debt must be created for all debt to be paid off and the system to keep going.

That's another story. For now just brainstorm and try to understand the "basic" rotations or "cycles" that occur because capital is shifting between the broad and basic major asset classes and the impact these shifts have and the things that cause them have.

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

Laying The Groundwork

You want a strategy that is mathematically correct. If you have numbers, you can use them, but you want to modify them. If you plan to take a stock trading strategy and convert it to an option strategy, you certainly can. Simply calculate the would be return for several possible outcomes and plug the numbers in the spreadsheet. The spreadsheet is the bulk of the work, but once you have it, it will work for you.

So you come up with a strategy of how many trades at a time maximizes your return. You then see the total capital at risk.

The key is to see the cash on the side and make sure you find some way to tie up MORE than that. Particularly as it relates to any asset with "risk". I have used conservative numbers I feel when running this strategy, but I will till plan on using generally around half the percentage. I have verified that doing so is correct, and actually 10-11 assets in the portfolio really maximizes it, however I wanted to reduce the position size to account for the volatility that will increase the fees when my position size is lower, while also providing a more stable strategy.